*By Victo Silva and Tulio Chiarini

*By Victo Silva and Tulio Chiarini

Recently, in partnership with Leonardo Ribeiro we published the article “Understanding the Brazilian platform economy: trends and regulatory challenges" in the magazine New Economy from the Federal University of Minas Gerais. Our objective was to profile Brazilian digital platform companies and discuss the options and challenges for regulating them.

The unprecedented survey of data on these companies in Brazil revealed the existence of more than 500 companies controlling digital platforms. These platforms represent an organizational model that fosters, manages and controls a network of economic agents, facilitating transactions between two or more groups and are present in all sectors, such as Singu, in beauty and well-being services, or Loggi, in the goods delivery sector

While consumers enjoy the conveniences offered by platforms, the private sector sees them as points of friction in networks online, capable of channeling user data streams for various purposes. As data is the primary source of digital innovation, platform companies are well positioned to mine and exploit this raw material directly at the source.

The survey carried out raises interesting questions, such as the relevant presence of startups based on this model. The 556 platform companies mapped by the authors are distributed across a large number of sectors, according to the Table 1.

The “commerce and shopping” category is the largest, including a wide range of marketplaces, from the most general ones, such as Magalu and WoodWood, to niche ones, such as Trocafone and InstaCarros. In second and third place come community social networks (such as Umatch) and medium services, such as cloud services. Another interesting fact is the penetration of “platformization” in highly regulated sectors, such as education, health and finance: together, these three sectors account for 10% of all Brazilian platform companies.

Source: Silva, Chiarini, Ribeiro (2024a). Data sourced from Crunchbase. Note: Companies can belong to multiple industry groups, so there is double counting. (1) Auctions, classifieds, collectibles, consumer reviews, coupons, e-commerce, e-commerce platforms, flash sale, gift, gift card, gift exchange, gift registry, group buying, local shopping, made to order , marketplace, online auctions, personalization, point of sale, price comparison, rental, retail, retail technology, shopping, shopping mall, social shopping, sporting goods, sales and concessions, virtual goods, wholesale. (2) Adult, baby, cannabis, children, communities, dating, seniors, family, funerals, humanitarian, leisure, LGBT, lifestyle, men, online forums, parenting, pets, private social networks, professional networks, questions and answers, religion, retirement, sex industry, sex technology, social, social entrepreneurship, teenagers, virtual world, marriage, women, young adults. (3) Cloud Computing, Cloud Data Services, Cloud Infrastructure, Cloud Management, Cloud Storage, Darknet, Domain Registrar, E-Commerce Platforms, Ediscovery, Email, Internet, Internet of Things, ISP, Location Based Services, Messaging, Music Streaming, Online Forums, Online Portals, Private Cloud, Product Search, Search Engine, SEM, Semantic Search, Semantic Web, SEO, SMS, Social Media, Social Media Management, Social Network , unified communications, vertical search, video chat, video conferencing, visual search, VoIP, web browsers, web hosting. (4) App discovery, apps, consumer apps, enterprise apps, mobile apps, reading apps, web apps. (5) Blogging platforms, content delivery network, content discovery, content distribution, creative agency , DRM, e-books, journalism, news, photo editing, photo sharing, photography, printing, publishing, social bookmarking, video editing, video streaming.

Although the sector varies, the type of platform adopted by Brazilian platform companies seems to mostly follow the transactional model, to the detriment of the innovative model (table 2). Transactional platforms reorganize previously existing markets, while innovation platforms create digital markets by offering third parties frontier resources to access a technological substrate (EVANS; GAWER, 2016). In simpler terms, innovative ones create an ecosystem of co-creators (like Google with its Android/Play Store platform and millions of independent app developers), while transactional ones are merely intermediaries in a transaction (monetization occurs via a fee on, say, a delivery service). It doesn't take much elaboration to understand that the former generate more value and appropriate it.

When we look at national platform companies (Table 2), we see the dominance of the transactional model. The question then arises: where are the Brazilian innovative platforms?

Market, technological complexity and risk

We still don't know the reasons that lead Brazilian companies that control digital platforms to opt for the “more lean” of transactional platforms, but it is possible to raise some hypotheses.

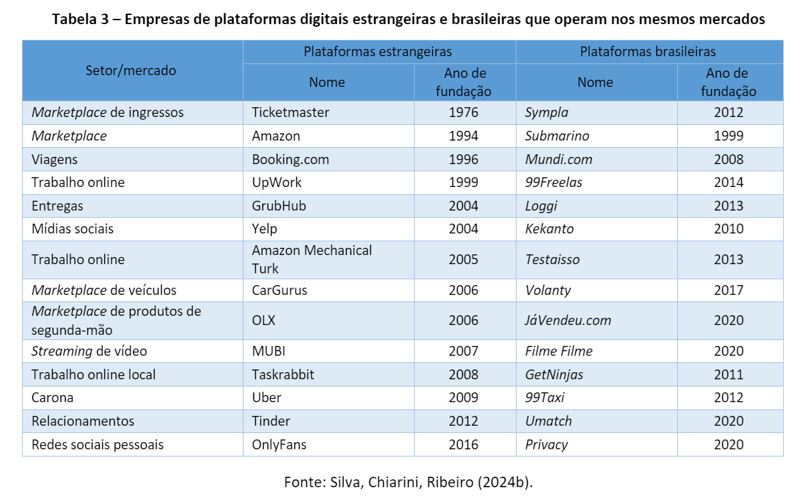

The first is related to the market and the competition faced by each type of platform. Brazil started developing platforms relatively later compared to the United States. A notable exception is the search engine sector, where the platform Where? preceded the Google in three years. However, in general, Brazilian platforms tend to emulate initiatives that emerged abroad, especially in the United States, according to Table 3.

Being the first in a market is an advantage recognized by innovation studies. In the era of digital platforms, being the entrant is even more crucial due to network effects, which loyalty (lock) consumers and users to a consolidated platform. Giants like Google, Amazon and Apple have built entry barriers so high that they make it difficult for Brazilian entrepreneurs who have ventured into the platform economy to compete.

The strategy of Brazilian companies, then, has been to direct platformization to sectors that are naturally protected from competition with these giants, due to the characteristics of the market in which they operate. For example, iFood leverages local network effects: it makes no difference, for example, for restaurants in Belo Horizonte how many drivers Uber Eats can mobilize in San Francisco, California. However, even operating locally, iFood had to fight a battle with Uber Eats city by city (and continues to face competitors, such as Colombian Rappi and regional platforms such as Aiqfome). For innovative platforms, such as Apple, its iOS and the Apple Store, network effects are global. A competing app store would have to be more attractive to consumers than the Apple Store, which mobilizes developers from all over the world. In other words, the competitor would have to break the strength of Apple's global network effect.

Another hypothesis is related to the degree of complexity for technological development: transactional platforms, as they act mainly as intermediaries in transactions, require less investment in technological development and infrastructure, becoming a more attractive option in a scenario of limited resources. Related to this hypothesis is the limited availability of risk capital and investments in innovation in Brazil, which may restrict the ability of companies to develop innovative platforms, which require a robust ecosystem of co-creators and greater investment in research and development. As on innovative platforms all products and services are co-created with complementarians (think of game developers and Sony), a failure in management can lead to the collapse of the ecosystem. As the risks are greater, more risk-sensitive capital is needed.

These hypotheses help to explain why transactional platforms dominate the Brazilian scenario, but they also highlight the need to create more favorable conditions for the emergence of innovative platforms, which can generate greater value and boost innovation in the country.

*Victo Silva is a researcher at think tank from ABES and Post-doctoral fellow at Radboud University (Netherlands). PhD in Scientific and Technological Policy from the State University of Campinas (2022), Master in Scientific and Technological Policy from the State University of Campinas (2018).

*T

References

EVANS, Peter C.; GAWER, Annabelle. The Rise of the Platform Enterprise. A global survey. , The Emerging Platform Economy Series No. 1. New York: [sn], 2016.

Silva, V., Chiarini, T., Ribeiro, L. (2024a) “Understanding Brazil's Platform Economy: Trends and Regulatory Challenges”. New Economy, vol. 34, p. 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6351/7958

Silva, V., Chiarini, T., Ribeiro, L. (2024b) “Platform economy: The emergence of Brazilian companies controlling digital platforms”, in Kubota, L. (org.), Digitalization and Information and Communication Technologies : opportunities and challenges for Brazil, IPEA/ECLAC.

Notice: The opinion presented in this article is the responsibility of its author and not of ABES - Brazilian Association of Software Companies