*Por Victor Silva

*Por Victor Silva

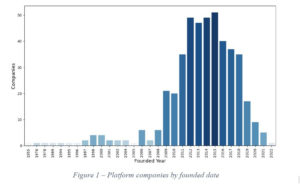

In recent article, Silva, Chiarini and Ribeiro conduct a pioneering survey of Brazilian companies that control digital platforms. The authors understand by “platform company” the one that controls a virtual interaction space that promotes connectivity between one or more groups, and that is based on network effects. From this perspective, platform companies are not just social networks (although a large part of the debate today understands that a digital platform is the same as a social network), but rather, they are companies that control platforms for the transaction of goods and services in general. , such as used cars, access to gyms and information. The authors located 556 platform companies in Brazil, mostly founded between 2010 and 2020 (as shown in figure 1), a sign that the country has not missed the platforming bandwagon: the diffusion of this new business model and this new paradigm of organization of

socioeconomic activities.

However, the firmographic data[1] of these companies are worrisome in two ways. First, Brazil does not originate any infrastructural digital platforms, that is, those that provide essential services to other platforms and other businesses (eg, Amazon AWS). With the exception of China, this is a feature that Brazil shares with the rest of the world, as the main infrastructure platforms are North American. Another worrying fact is that platform companies in Brazil are small. This trait can be linked to several factors, but one specific trait has been vehemently ignored by public policy managers: the online job market is a global market.

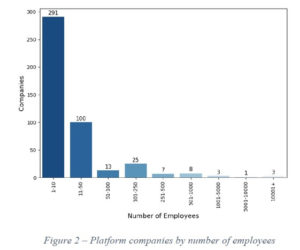

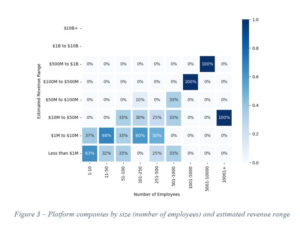

Figures 2 and 3 below demonstrate that most platform companies are microenterprises. Of the 556 companies located, 65% have between 1 and 10 employees. Other 22%s have between 11 and 50 employees. That is, only 13% of the companies have more than 50 employees. There is a pretty clear correlation (correlation does not imply causation!) between the number of employees and the range of income. Figure 3 demonstrates how companies with fewer employees are also those with more timid revenues. For example, of the platform companies that have between 1 and 10 employees, 63% have an estimated annual revenue of less than US$1 million, while 37% have an estimated annual revenue of between US$1 and 10 million.

A strong candidate for explaining the small size of Brazilian platform companies is the difficulty in finding human capital to grow. And platform companies are just a subset of IT companies, which in turn are a subset of all national companies that today increasingly rely on IT professionals not just for operations but also for innovation. The lack of skilled labor in IT in Brazil is a chronic problem. In the IT Forum alone, there are many articles commenting on the difficulty of finding good IT professionals. In 2010, the editorial office published a text which mentioned that the “evolution of telecommunications demands qualified professionals”. In 2018, it drew attention to another text about how the “Lack of qualified professionals challenges the advancement of IoT in agritechs”. In the same year, Fabiana Rolfini questioned “Why is there a lack of skilled labor in IT in the country?”. And, in 2021, the portal published that the deficit of IT professionals in Brazil should leave more than 408,000 jobs empty by 2022, identifies a survey by Softex, a social organization dedicated to promoting the IT area of the TechDev Paraná project. Due to staff shortages, accumulated losses over the last ten years (2010-2020) reach R$167 billion.

There are even a large number of articles highlighting as solution for this chronic deficit training by the companies themselves due to the inability of the educational system to train these professionals and/or mitigating solutions how to identify “adjacent skills” in available IT professionals. Without questioning the viability of these strategies at the micro level of the company or HR, the problem is much more structural and, therefore, requires adequate answers. Telemigration, term used by Richard Baldwin in his book The Globotics Upheaval: Globalization, Robotics, and the Future of Work, will only increase in the coming years.

The elephant in the room: telemigration and the global stratification of service flows

In ongoing research, Silva, Heusinkveld, Herrmann and Vermeerbergen interviewed 40 Brazilian IT workers who obtain work through the online platform upwork. Of these, without exception, all mentioned that the possibility of earning in dollars or euros attracted them to this type of freelance work. However, many also commented that they are looking for remote “full-time” jobs, that is, that they intend to work for an American or European company, receive in foreign currency and spend in reais. Basically, this guarantees the worker a salary five times stronger than what he would get in a similarly paid job in Brazil.

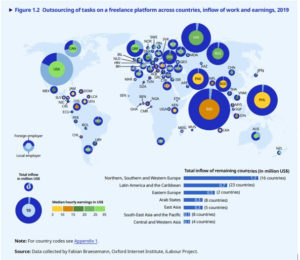

These online work intermediation platforms have grown a lot, especially after the pandemic. Brazil no longer suffers from telemigration because the fluency of English in the Brazilian population is low. It is no coincidence that India, a country where English is widely spoken, leads the world as the largest exporter of online services, whether in IT or in other areas, as shown in the figure below, present in document recently published by the International Labor Organization.

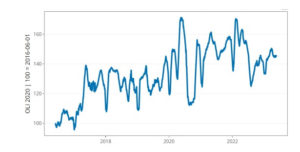

Today, it is estimated that, only intermediated by online work platforms such as Upwork, Freelancerdotcom and Fiverr, there are more than 160 million workers worldwide (Kassi et al, 2021). However, this estimate does not consider remote workers who are in direct contract with employers, so the number could be higher. In the figure above, Brazil appears as one of the countries in which there was a greater flow of dollars for payment of services via digital work platforms. In addition, the average salary is among the highest, indicating that these are professions with high added value that are “leaking” through networks to foreign companies. The Oxford Internet Institute calculates the online job index by monitoring jobs posted on major online job platforms. Between 2016 and 2023, the index grew by almost 50%, indicating a strong expansion in the demand for professionals.

Source: Oxford Internet Institute, Online Labor Observatory

The federal government, through the Secretary of Science and Technology for Digital Transformation of the MCTI, recently announced a program that will invest more than R$ 30 million to train IT professionals, exclusively focused on cybersecurity. The initiative is great and assumes for the state the mission of promoting the training of human resources. However, as argued, there is no policy designed to deal with the progressive leakage of professionals through digital channels to companies that pay in dollars or euros.

As long as training policies are not designed considering the new reality of a global online job market, there will be no resolution for companies that need good IT professionals in Brazil. The best professionals, trained both in IT and in languages such as English, will have a great incentive to work for a foreign company. There are certainly obstacles to this type of work (such as distance from the employer, time zones, cultural differences and the impossibility of establishing a hybrid routine). But at the end of the day, with salary being a decisive element in the IT professional's decision, the balance is very unbalanced for foreign companies. With the advancement of connectivity in Brazil and education (and fluency in English), the problem tends to get worse. Just as when capital flows were released, Brazil needed to reinvent its financial system (eg., paying exorbitant interest to maintain a balance in this market; creating an exchange reserve to avoid shocks), the labor market today is taking great steps towards globalizing remotely. It is necessary to think about multilateral policies to order this new global architecture of the flow of services, but also national policies to face this new challenge.

[1] Firmographic Data is a collection of descriptive attributes used by B2B organizations to segment their market and discover their ideal customers. This data helps categorize companies according to geographic location, industry, customer base, type of organization, technologies used, etc.

References:

Kässi, O., Lehdonvirta, V., Stephany, F., (2021). How Many Online Workers are There in the World? The Data-Driven Assessment. Available at SSRN: link 1 and link 2.

Silva, V., Heusinkveld, S., Herrmann, A., Vermeerbergen, L. “Identity work of online gig workers: social identities in a process model” (in preparation for Human Relations)

Silva, V., Chiarini, T., & Ribeiro, L. (2022). The Brazilian digital platform economy: a first approach.

*Victo Silva is a researcher at the ABES Think Tank and a postdoctoral fellow at Radboud University (Holland). PhD in Science and Technology Policy from the State University of Campinas (2022), Master in Science and Technology Policy from the State University of Campinas (2018).